I can’t get started without first extending a huge thank you to everyone who has reached out in response to this undertaking. I’ve received words of encouragement, advice, and constructive criticism. I’ve received coaching and mentoring offers, and people have offered to take time out of THEIR day to review my VODs and provide feedback. It’s truly a special feeling. The Overwatch University reddit deserves a special shoutout of its own for being especially welcoming.

One quick note: I changed “Meta Learning” to “Super Learning” so that people don’t oversimplify things and thing I mean simply “learning the meta” to get better.

Now that that’s out of the way, I can begin to tell you about how I completely ignored everyone to kick my first week off. I replied to everyone who reached out and said that I’d be in touch (I promise that I will be!), but I wanted to have at least one week where I ran through the learning principles on my own before I started taking steps with others’ help. I took advice and the results of my interview questions, of course, but I didn’t let anyone get hands on with my games.

So, I tried to do things on my own. I completely shit my pants. I performed so badly in the first week of competitive that I debated hiding away from this project so that I didn’t have to tell the internet about how things went.

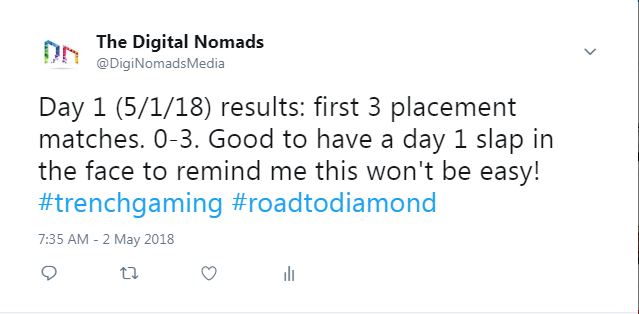

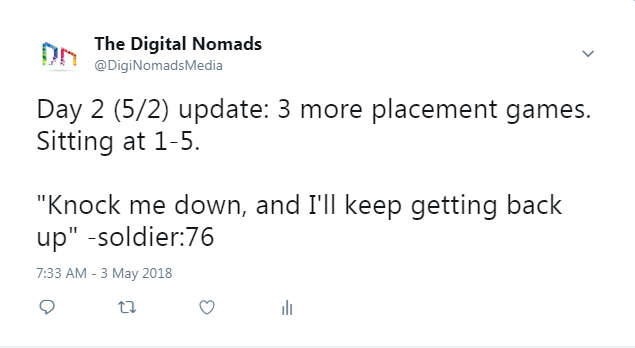

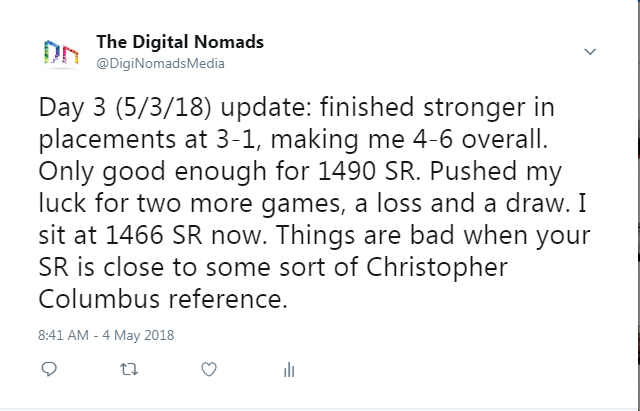

What this train wreck resulted in was a great lesson in humility, adversity, adaptation, dealing with tilt, and owning my losses and mistakes. You’ll notice that this introduction has been extended to 5 paragraphs because I’m delaying telling you how bad my first week was. Why don’t we just dive right into it, and let my twitter do the talking:

This is just the tip of the iceberg. It gets worse, all the way down to what I sure hope is rock bottom:

If I could characterize the experience so far, I’d say it’s like preparing endlessly to run a race, finally getting up to the starting block, and getting a cramp as soon as the gun goes off because you didn’t stretch before.

To elaborate, I had the building blocks in place, my plan for learning was set, I followed the recipe I set for myself for training, and then when I actually got into games, I fucking PANICKED. I forgot everything about my learning. I strained myself and forced everything. I played like the most rigid asshole you’ve ever seen. Soldier ulting right in front of roadhogs who could hook me, D.Va ulting with a shield tank clearly ready to address it, you name it.

In short, I deserve my rank, and I have nobody to blame but myself. I could have blamed my teammates, team comp, teamplay, circumstances, there’s a million bullshit things that I could have said, but none of them would be the right answer. The trenches exist, but you always put yourself there. No one else puts you there.

Now that we’ve got that out of the way, it’s time to update my learning recipe based on what I’ve discovered from new advice and a week in complete Hell. I’m sure you’ll find some excellent lessons sprinkled in here.

Communications

Holy Fuck. I paid FAR too little attention to this element. There are so many nuances in play here that I never would have even thought to mention before I dove into this adventure. This is probably the area I’ve learned most about during my “baptism by fire” period. Here are some of my most important findings:

Mute the Dickheads

Plain and simple. You have to do it. You absolutely have to. The energy that you put out to your team is your choice. If you’re being negative or a complete dickhead, you’ve made a choice, whether you’re willing to admit it or not. Even if you’re being negative in response to someone else’s toxicity, it was your poor choice to react. You’re not absolved from blame. Your pretentious sighs over voice chat count as toxicity, too.

Thankfully, Blizzard gives you two great two tools: the mute option, and the “avoid as teammate” function, that make hearing these kinds of people now, and into the future, a choice as well. It is imperative that you use them. A raging, toxic teammate on my team seemed to be as good as a loss most of the time. If I engaged with them or entertained them in the slightest, I started to feel worse, and then play worse. Same goes for my teammates that weren’t acting like psychos.

The effects didn’t just last for one game, either. It spread over several. I could feel the anger causing me physical pain, feeling like my blood was truly boiling. I wanted to kick my damn dog for looking at me funny. There’s actually quite a bit of meaning to someone being called “cancer,” though people float the term around carelessly. If you don’t cut it out at the source, at the moment it’s noticed, it will spread over you and your teammates’ current and future games. Get rid of their ability to affect you, encourage your teammates to do the same, and move on. Your progress depends on it.

Too much communication can be just as bad as too little communication

This one was a very interesting but important find. The one recommendation that I received quite a bit at the outset of this journey was to make sure I communicated with my teammates. I definitely did look back with some regret when I didn’t let my teammates know something that could have saved them in the moment. I never had anyone tell me that too much communication could be bad, but I saw that happen quite a few times.

With new players, a little direction can go a long way. Too much direction, however, can lead to problems. I generally try to stay quiet unless it’s necessary on comms. I had some teammates, though, who would report everything that was happening to them as if they were shoutcasting their own autobiography. They call out every time a hero fires a bullet in their direction. They announce every single movement they’re making. They’re just saying things that are plainly obvious or seen by everyone. I appreciate the commitment to being a team player, but I wish I could smack these people with a rolled up newspaper.

There’s a “cry wolf” scenario that happens with this tactic. If you’re shouting out every single problem you’re dealing with, you’ll be less likely to get what you need from your teammates right when you need it. It’s impossible to react to every single thing. People who are still learning the game will end up with more confusion than direction from something like this. Moreover, if someone has to talk over you to say something that’s really important, vital communication has a bigger chance of being lost in the chaos.

If you feel like you may have just identified yourself as one of these people, try to keep things simple. If someone is attacking you, and you can get away without help, do it, and don’t make a big deal about it unless you need to identify that enemy’s position to your teammates. “Mercy is 1 hit” is good enough to signal someone to finish them off. “Reaper behind you, Rein” says everything your teammate needs to know in 4 words. Keeping things simple will allow everything to be more efficient and crisp.

Though I wouldn’t consider communication an 80/20 (see my previous articles for that definition), it is a hugely important factor in your improvement. Making better decisions for yourself by listening to the right people, and making your teammates’ decision-making easier by communicating is definitely a big way to win games and climb ranks.

Deconstructing Deconstruction

As far as my process of deconstructing Overwatch goes, I think my main “pillars” of knowledge were pretty spot on. Learning the maps, positioning, how to aim, and ability management are still in my mind the most important things to focus on.

What a lot of my interviewing and advice-seeking has yielded, however, is the idea that I need to “deconstruct my deconstruction.” I found the most important pieces, but I didn’t break them down into the “minimal learning units” that I described when defining deconstruction. I knew this process certainly wasn’t yet polished, but I really have only hit the tip of the iceberg so far. Let me provide an example:

When learning a map: Instead of just knowing the layout of the map, I need to ask some more detailed questions.

- Where are the health packs? How long does it take me to get from one health pack to another in critical situations?

- Where are the perches located for heroes like Soldier, Widowmaker, and Hanzo?

- Where are the chokepoints that I’ll need to push through as a tank, or will love to fire into as a hitscan?

- Can Orisa, Lucio, Pharrah, Roadhog, Winston, D.Va knock me off an edge or down a hole?

- What type of game mode occurs on this map?

- If it’s an escort map, what path does the payload take? Where are the checkpoints located? If I’m a hero that doesn’t normally sit on the payload, where are my vantage points at each payload position?

- If it’s a control map, where are the two points located? If I’m defending, how long of a walk back is it to the first point? (I’ve found this one to be crucial. Dying at objective A on Volskaya Industries is about a 30-60 second walk back as an Orisa. Knowing that, it’s not smart to trade your life for one attacking player’s life more than 9 times out of 10.) Where will players funnel in or sneak by if I’m on defense? How far will I have to walk if I die on objective B when attacking? Where will Torb, Bastion, or Orisa set up?

- If it’s King of the Hill Best of 3: Will my hero be effective in all 3 (or sometimes, just 2) locations, or will switching between rounds be high value? What heroes can take advantage of the open space around the point?

Boiling down map learning even further allows me to truly get what I need from a walkthrough of a map. I’ve been doing a walkthrough of an empty custom game to get further acquainted with every map, and I now run through the above bullet points every time I do this. I’ll cover one map per day of play. It also gives me a better idea of which heroes I should consider, and how I should play when I’m at each map. Overall, I now feel much less like I’m wandering aimlessly when I do map analysis.

Revisiting Hero Selection

When I look back at my earlier articles and compare them to my past week’s results and advice received, I realize that I wasn’t really following my own formula when I came up with my list of heroes to focus on. I also used some very laughable assumptions when developing the list.

Abandoning comfort once and for all

I picked my heroes for the list almost entirely based off of comfort. For example, many people mentioned that D.Va and Roadhog, though perfectly fine heroes, certainly aren’t the highest value picks in their category. They function more as “off tanks” rather than “main tanks.” They don’t provide a reliable shield. If no one else on my team picks a tank, I’ve made a bad choice by sticking to one of those. I picked them because I was most comfortable with them.

To clarify, it’s not bad to say “I want to be an off-tank specialist.” For me, though, someone who wants to be as efficient as possible and play heroes who will provide the most value both overall and in the moment, off-tanks don’t cut it most of the time.

I was the first one to say that picking heroes based on comfort or level of enjoyment was the wrong way to go about climbing. I then, without really knowing it, proceeded to announce my intention to ignore that statement in the same breath. I needed to call myself out on this one. Comfort is a direct trade off for learning at times. This was one of those times.

At this point, switching things up costs nothing.

I should have designed my hero list without relying on any previous information from my time as an Overwatch player. What works in quickplay doesn’t necessarily work in competitive. I also just haven’t played enough Overwatch to say I’m better at one hero over another. I haven’t even played Symmetra once, for Christ’s sake. I’ve never completed a full game with Bastion. I’ve played under an hour on countless heroes.

The opportunity cost to me of learning a new hero and staying off some of my regulars is almost zero. The amount of potential upside is incredible. I don’t undo any of the progress I’ve made with heroes I’ve played a lot, and I add more heroes, and therefore, more value to my portfolio.

It’s probably more likely that I haven’t found my best hero, or even my top 3 heroes yet. I haven’t even played Symmetra once, for Christ’s sake. Because of this, I’ve realized that it’s not the right time to be rigid with my hero choices. Instead, I need to put my focus on which heroes excel in which roles on which map, and which heroes are high value in the most situations.

Orisa, for example, has found a nice place in my hero pool because I started to realize how versatile she was in so many game modes and maps (plus, I’ve learned that people love playing with shields on their team).

Ditching the list… for now.

For now, since I’ll be taking coaching sessions and VOD review feedback within the week, I’m going to suspend the use of a rigid list of heroes for competitive. If a coach recommends a hero during a session, I’ll take their recommendation. I’ll also use weekends to get some quickplay time in on heroes I don’t normally play. This way, I can learn how they work when I’m at the controls, when they’re my teammate, or when they’re my enemy.

I thought that learning too many heroes might cause anxiety or overwhelm, but I’m finding that there’s too much to be gained in getting an intimate feel for heroes that are alien to me, at least until I’ve hit a certain number of hours played. Jamming Soldier into bad team comps or game modes produces more anxiety than that.

It’s okay to be wrong. In fact, it’s necessary.

Though I feel pretty stupid for the assumptions I made, there’s so many learning opportunities, and so many opportunities to take my progression in this game to new levels. It’s a reminder to me that sometimes we have to look at our outset assumptions and ask, “what if I did the opposite?” We’ll never be completely right from day one, but we’ll always be wrong if we don’t admit flaws in our process, adjust, and adapt as they are noticed.

The One Pager- Harnessing compression

The biggest thing that I felt plagued by in the first week was execution. That seems pretty normal to me. To elaborate, I was able to come up with a formula for learning this game, which is all well and good. When it came to applying my formula, however, I was a colossal failure. As soon as a game began, I was like a teenager on their first date. Everything that I had rehearsed vacated my mind immediately, and suddenly I was nowhere near as smooth as I thought I was. I stuttered through many awkward, demoralizing experiences where my mind’s nervous autopilot overtook everything I tried to feed it.

How to remedy this? For one, playing more games will certainly calm my panicked mind. When more things become second nature, I’ll be able to focus more on my formula in real time. But I don’t just want to wait for that to happen. I want to speed things up.

The solution, though I haven’t developed one just yet, will be a one pager. Another excellent Tim Ferriss principle (references to him are located in earlier articles and the end of this one) is compression. Designed to simplify things further still, compression focuses on getting all of your most important learning pieces on one easy to read page.

The plan, when finished, is to have this one pager available next to me while I play. I’ll read it every time I hit the queue button, every time I die, and at the end of every round. This should help keep what I need to be thinking about at the top of my mind as often as possible, to help foster better decision making in the heat of the moment.

Compression will help me keep things simple, sure, but it’ll also allow me to have something that I’m able to prepare and reflect with in the blink of an eye. Not only will it work me toward more mindful play quicker, it’ll allow me to spot my own mistakes and cast out bad habits quicker as well. If you have any input on what should go on the one pager, reach out and let me know!

This week’s wrap up

I would feel confident in saying that what I’ve written here covers far less than half of the learning I’ve undergone by sucking shit on my own for a week. I covered what I believe to be the things that stuck out to me the most.

Though I feel bad that I tossed 3-400 SR out the window, I wouldn’t trade the position that I’m in for another one. Constant success teaches you nothing. Adversity and accountability is where you grow. Owning my mistakes and making them public will make this project the learning tool that I want it to be. Hopefully that will make this series read well as a tool for learning, but also personal growth by the time it’s finished.

I’m excited to bring mentors and coaches into the journey, and have some VODs out soon, so that everyone can witness the train wreck firsthand rather than hearing my account.

Credit Where it’s Due

I just want to end by giving Tim Ferriss the deserved shoutout that I’ve owed him for several posts now. He is the main inspiration for me to take on this journey, and a large percentage of my formulas are adapted directly from his work. I’m mainly “porting” it over to the gaming world. I hope that I’m doing him justice. Check out his podcast here (it’s only been downloaded over 300,000,000 times, so he could use a few more), and check out some of his books including: The Four Hour Work Week, Body, and Chef (the 4 hour chef contains a lot of the “meta learning” information that I’ve used here).

Thanks yet again for reading. Your comments and feedback have fueled this project and helped keep it active and thriving. I can’t do this alone, and I haven’t. I will try to maintain one update per week. Best wishes, and happy grinding this week!